Malcolm's 1994 model for measuring edge responses

Malcolm (1994) developed a model that we believe offers the best framework both for determining the distance of maximum edge influence and dealing with the issue of complex edge geometry. Malcolm’s model has been cited numerous times (139 as of Jan 2010), but we found no evidence that it has ever been implemented (beyond the original publication). The model’s solution was useful in that it can incorporate actual patch geometry and also results in a non-linear solution with the exact type of threshold effect that has been sought by many in the past. Further, this modeling approach allows complex geometry to be factored in either when measuring edge effects in the field or when predicting edge influence throughout a landscape. Ultimately, Malcolm’s solution is useful because it returns parameters that are of interest to most researchers: estimates in the habitat core (k), the maximum distance of edge influence (Dmax), and a parameter describing the effect of the edge (e0). We can only speculate as to why such a useful model has never been applied (beyond the original paper) over a 15 year period, but we suspect that at least part is due to the mathematical complexity of applying the model in real landscapes.

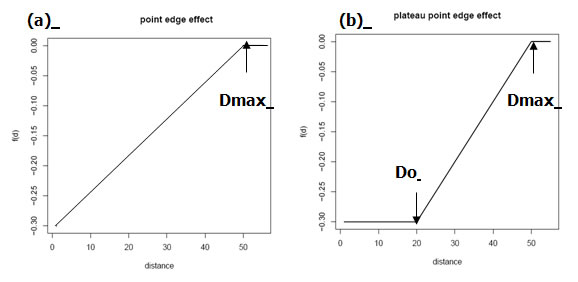

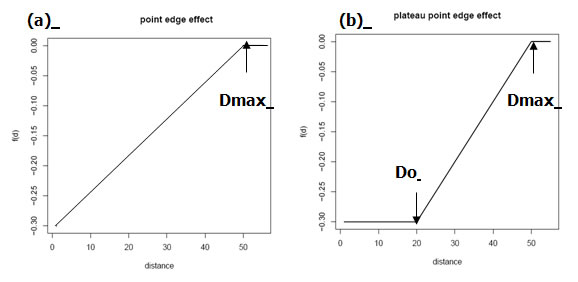

The basic model considers that every point along an edge can exert an ecological influence (say on animal density or plant height) on any point in space, up to some maximum distance. In Malcolm’s original model this point edge effect was assumed to be linear from the edge to the maximum distance of edge influence (Dmax), at which point it was assumed to level off (see panel a at right). We have extended this model to allow plateaus at both the edge and the interior (see panel b at right) by adding an additional parameter, Do. Point effects are integrated across the entire edge at all distances less than Dmax to arrive at a predicted density (or plant height, etc.) at any point in space, as long as the configuration of all edges within the specified distance are known.

The basic model considers that every point along an edge can exert an ecological influence (say on animal density or plant height) on any point in space, up to some maximum distance. In Malcolm’s original model this point edge effect was assumed to be linear from the edge to the maximum distance of edge influence (Dmax), at which point it was assumed to level off (see panel a at right). We have extended this model to allow plateaus at both the edge and the interior (see panel b at right) by adding an additional parameter, Do. Point effects are integrated across the entire edge at all distances less than Dmax to arrive at a predicted density (or plant height, etc.) at any point in space, as long as the configuration of all edges within the specified distance are known.

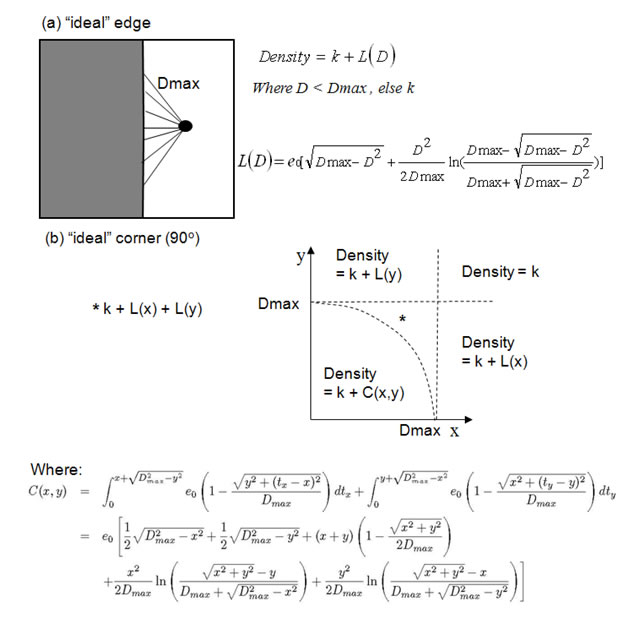

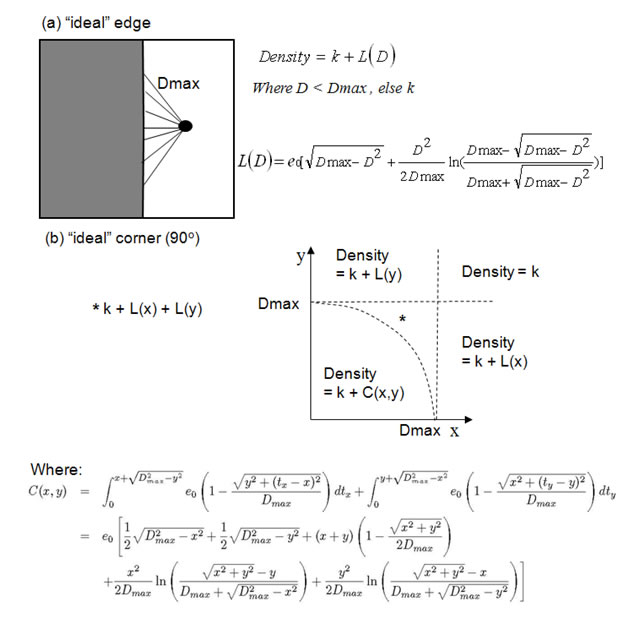

In the original paper, the only solution presented was for a point along an “ideal” edge that is perfectly straight, divides two habitats only, and extends to infinity in both directions (see panel a below). However, the model was intended to be used in more complex patch shapes, and Malcolm (1994) noted that the model could be used on patches of any shape. The solution for a perfect corner gives an indication of why this model has never been implemented in real landscapes (see panel b below). This solution is only applicable to a perfect corner and even a corner of slightly different geometry (e.g., 89 degrees) would require a different solution. In reality, a unique solution is required for every patch in a typical landscape (except, perhaps, experimental landscapes). Obviously, the task of individually finding a unique solution to every patch on the landscape is intractable.

To tackle both challenges, we developed an R package (“edgefx”) that, given a simple map of all edges within Dmax, calculates the solution and allows parameterization of and predictions generated from Malcolm’s model. Further, we implemented our four-parameter version of Malcolm’s original equation along “ideal” edges within the package. This function is useful because many edge studies establish transects along these types of edges (or simply assume they are “ideal”). The “edgefx” package also implements a simplified version of the EAM on a binary landscape to determine the effects of extrapolating edge effects where the complex geometry of the landscape is incorporated into the predictions, rather than considering only the distance to the closest edge (as the EAM currently implemented in ArcGIS does).

Read more about Malcolm's model (including a model test)

Download the R-package ("edgefx")

View a guide to the R-package ("edgefx")

The basic model considers that every point along an edge can exert an ecological influence (say on animal density or plant height) on any point in space, up to some maximum distance. In Malcolm’s original model this point edge effect was assumed to be linear from the edge to the maximum distance of edge influence (Dmax), at which point it was assumed to level off (see panel a at right). We have extended this model to allow plateaus at both the edge and the interior (see panel b at right) by adding an additional parameter, Do. Point effects are integrated across the entire edge at all distances less than Dmax to arrive at a predicted density (or plant height, etc.) at any point in space, as long as the configuration of all edges within the specified distance are known.

The basic model considers that every point along an edge can exert an ecological influence (say on animal density or plant height) on any point in space, up to some maximum distance. In Malcolm’s original model this point edge effect was assumed to be linear from the edge to the maximum distance of edge influence (Dmax), at which point it was assumed to level off (see panel a at right). We have extended this model to allow plateaus at both the edge and the interior (see panel b at right) by adding an additional parameter, Do. Point effects are integrated across the entire edge at all distances less than Dmax to arrive at a predicted density (or plant height, etc.) at any point in space, as long as the configuration of all edges within the specified distance are known.